Ellen Ranyard (“LNR”), Bible women, district nurses and informal education. Known for using innovative methods, Ellen Raynard brought about the first group of paid social workers in England and pioneered the first district nursing programme in London.

Ellen Ranyard (“LNR”), Bible women, district nurses and informal education. Known for using innovative methods, Ellen Raynard brought about the first group of paid social workers in England and pioneered the first district nursing programme in London.

Contents: introduction and background · Bible women · Bible nurses · management and organization · informal education · conclusion · further reading and references

A linked podcast is now available on The Red Heaven Oral History Archive. You can also access Lizzie Alldridge’s (1890) reflections on Ellen Ranyard’s achievements and legacy in the infed archives.

Let us sow them wherever we are able the imperishable seed of the word, broadcasting it in humble faith and prayer. (Ellen Ranyard 1861, quoted in Platt 1937: 1)

Ellen Henrietta Ranyard (1810-1879) was the daughter of an apparently prosperous (and kind) non-conformist cement maker – John Bazley White, and Henrietta White (formerly Clark). She was born on January 8, 1810, in Nine Elms Lane, which ran along the southern side of the River Thames close to Battersea. Ellen was the eldest of a large family of brothers and sisters (Kitty Alldridge 1890: 102). As a youngster, she ‘developed a taste for books and art, and a passionate longing for bringing out the best of what she felt was in her’ (op. cit: 103). She attended the Congregational church in Walworth but reports her mission history began when, at 16, she and her parents attended a Bible meeting at Wanstead (which must have been quite a trip then). There she met Elizabeth Saunders – ‘a gentle and loving soul’ – who became her friend and who later asked her a key question – what would she do with her life? Elizabeth stayed with the Ranyard family for a short while. She suggested that Ellen leave her painting and go with her to find out how many want a Bible. This is how Ellen White described what happened next:

This dear Elizabeth, however, had set her heart on the exploring walk, and she obtained my mother’s consent under protest, I remember, for she looked anything but fit for the exertion, and was made to take egg and wine as a fortifier before going out. So we set forth, she with a Bible in her hand and a prayer in her heart, and in her pocket a pencil and a little book, a page or two of which she had been ruling in squares while I had been painting by her side. Oh! that last walk in her lovely, holy, gentle life! It led her to her death, but me, at that unknown cost, to life eternal. She certainly gave prudence to the winds. We must have been out three hours, and we found the people in thirty-five houses on that day without a Bible

I came home, having seen for the first time how the poor live; their ignorance, their dirt, their smells – for we went upstairs to more than one sick-room ; and I heard my friend, in a way that I had never heard before (though religiously brought up), tell the good news of the love of Jesus to the consumptive and the dying. She spoke to them, but the Spirit of God carried the message home to me…

We finished our walk by a talk with an old woman in a filthy shop, who sold coals and greens, and there I never shall forget the odour; and the old woman was deaf and rude; but we actually turned homewards with thirty-five pence in our bag, and as many names in our collecting book, and as we reached our gate I saw that Elizabeth could scarcely stand… (I)n that walk we had both taken fever: mine proved to be bilious, and hers turned to typhus. {This was part of some notes left by Ellen Ranyard and included in Alldridge 1895: 103-8.)

When Ellen recovered, she returned to the homes she and Elizabeth had visited:

… collected the remaining money, which amounted to £6, and took it to a women’s Bible committee meeting at the British and Foreign Bible Society, of which her grandmother was president, and from which the thirty-five Bibles were procured and distributed by Ellen. (Williamson 2004: 60)

George Clement Boase (1896) reported that from her friend’s death, ‘Miss White regularly visited the poor, collected pence for supplying them with bibles, and interested herself in the bible society’. Her personal experience as a visitor, Frank Prochaska (1988: 48) has argued, looks to have stimulated her lifelong commitment to philanthropy. However, it also seems that her parents’ and grandmother were a significant influence.

Swanscombe

The White family moved to Swanscombe, Kent (between Dartford and Gravesend) close, again, to the River Thames. Here the ‘large family grew up, and gradually dispersed’ Alldridge 1895: 110). Ellen met Benjamin Ranyard (born February 10, 1803), also a non-conformist, who then lived in Westminster (he had been brought up in Kingston). They married on January 10, 1839, at York Street Chapel in Walworth (Williamson 2004) (now the Browning Hall). Ellen and Benjamin set up home in Milton Street just outside Swanscombe (1841 Census). Both were listed as having independent means. In later censuses, Benjamin Ranyard was recorded as a barge owner with 16 employees (1861) and a landowner (1871).

Between 1840 and 1846, Ellen gave birth to four children – Herbert (1840), Edith (1843), Arthur (1845) and Alice (1846). She also had a stillborn son (1841). Sadly Edith died in 1861 and Alice in 1865 (data from Find My Past). Arthur went on to attend the University of London and become a noted astrophysicist (click for more details). Herbert became a mercantile clerk and appears to have emigrated to New South Wales, Australia. There he married Mary Ann Crocker in 1865 and they had six children (one of which was named ‘Benjamin’ and another ‘Ellen’!) He died in 1911 (see WickiTree). Ellen also remained active outside the family – for example, holding mothers’ meetings ‘amongst the country poor’ and retaining a strong concern with the work of the British and Foreign Bible Society and similar bodies. She also kept her interest in painting. Significantly, she began to write, at the suggestion of the Rev Thomas Phillips (the Bible Society’s Jubilee Secretary), what became The Book and its Story, a Narrative for the Young (E. L. R. 1853).

In 1853, and writing as E. L. R., Ellen’s reflections on the Bible Society’s work (which began formally in 1804) were published. At 474 pages in the US edition, it was a substantial piece of work. It explored the history of the Bible, the impact of it being printed, and the work of the Bible Society. The opening ‘advertisement’ (by T. P. – ‘Rev. Thomas Phillips, Jubilee Secretary’) argues that while it ‘professes to be a narrative for the young’ we would be ‘greatly mistaken if it be not regarded as a book suited to all ages, and perused with interest by all who love the Book whose Story it gives’. The Book… proved to be popular and established E. L. R.’s reputation as a writer and commentator. However, it was her organizing abilities and her orientation to developing practice that then became more central.

When developing her work and thinking, Ellen Ranyard could also draw upon the experience of those pioneering City Missions. The first of these missions was founded by David Naismith (1799-1839) in Glasgow in 1826. It was followed by City Missions in Edinburgh (1832) and London (1835). The model they provided was significant, as Ellen Ranyard noted in her book The Missing Link. , It also appears to have influenced some of those involved in setting up the YMCA in 1844 (see Clyde Binfield 1973 Chapter VIII). She wanted as many people as possible to have access to a Bible (and to read it), and for them to develop or receive the means to live healthier and happier lives. However, as we will see, her experience of the streets and homes of the Seven Dials area gave her plans a new twist and sharper focus.

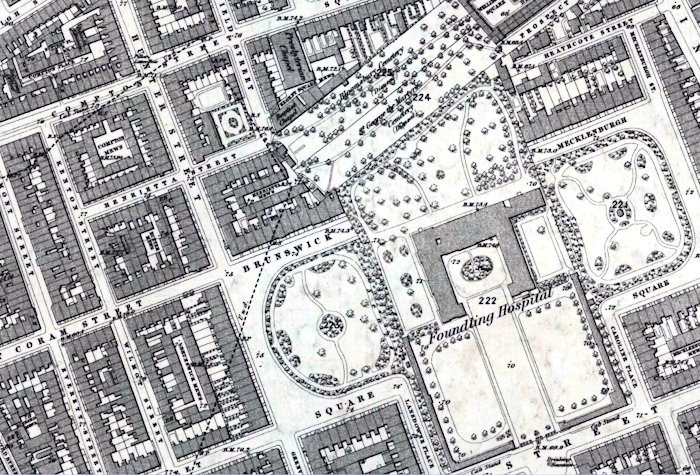

Brunswick Square

The family moved into central London in 1857. Their house was close to the Foundling Hospital and Coram Fields [13 Hunter Street, Brunswick Square]. It was also just under a mile away from the Seven Dials area that would become the focus of Ellen Ranyard’s work for some years. Arthur lived in the house until he died in 1894.

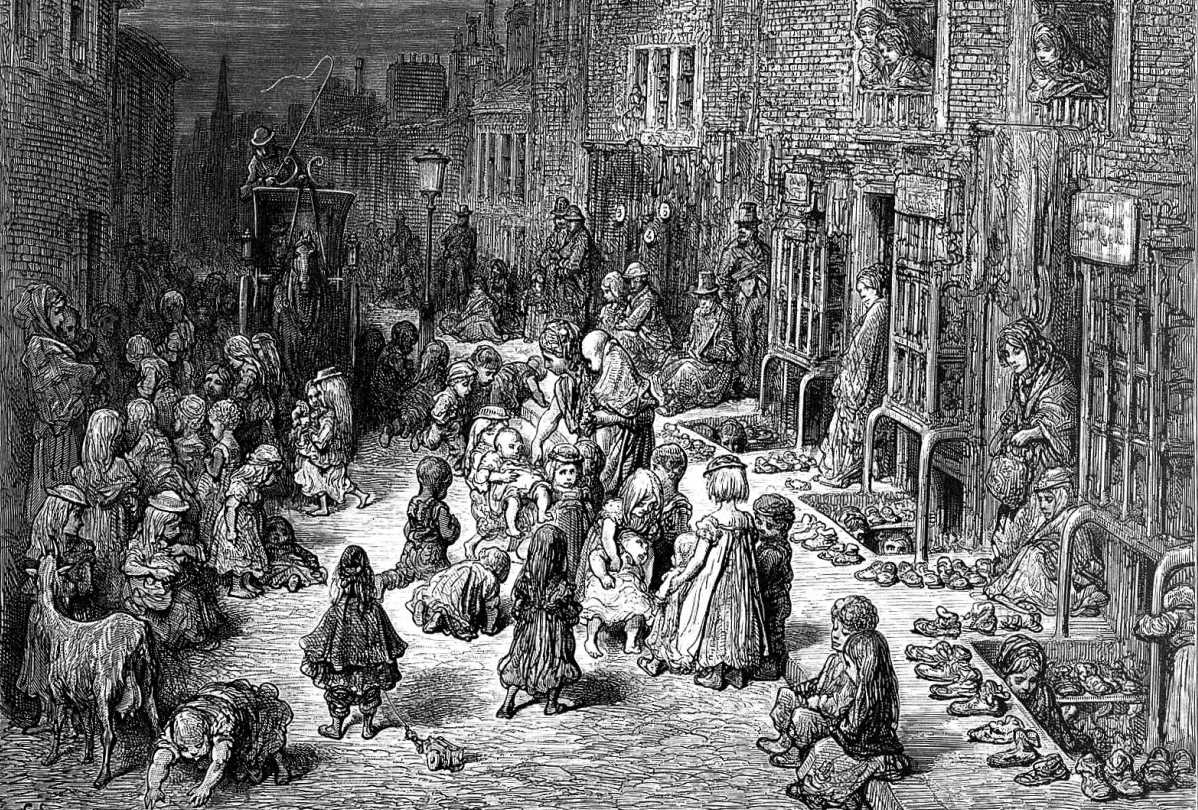

One of the first things that Ellen Ranyard did on her arrival was to visit the Seven Dials – and the experience confirmed her resolve to develop work locally – and establish an organization to facilitate it. This is part of what she wrote:

The streets are filled with loiterers and loungers. Lazy, dirty women are exhibiting to one another some article of shabby finery, newly revived, which they have just bought. We search in vain among the ragged, sallow children for a bright face or a clean pinafore. There is not a true child-face among them all; nothing speaks of God or Nature but one basket of flowers with which a man happens to be turning the corner of the street.

Some of the dingy windows of those upper floors are open; and, oh, what dirty, haggard forms are peering out. Many a pane is stuffed with rags, and all around bespeaks a want of light and air and water. We looked up the dark courts and alleys, which had poured forth those squalid children, and which link the seven streets together, and would fain have entered, but there was a something about them which seemed to say, ‘ Seek no farther, or you may never return’. (Ranyard 1859: 3-4)

As we will see, one of the key things she recognized was that supplying poor people, particularly women, with Bibles and support to change their lives ‘would best be accomplished not by city missionaries, but by working-class women’ (Williamson 2004). She also sought out local people. The fact that they knew the area, and were likely to have faced many of the same issues as the people they are approaching and working with, added to the likelihood of acceptance. Crucially, the ‘Bible women’ were to be paid, thus both bringing money into the area and giving hope that some others could gain similar paid employment.

All this, in turn, needed organization. Thus, Ellen established the Bible and Domestic Female Mission (known by various names over the years including The Ranyard Mission. Click for details). Her role within the organization was that of Honorary Secretary and Lady-Superintendent. The MIssion became known for its innovative approaches and the scale of provision (which we discuss in the following three sections). Crucially, they worked in some of the most deprived areas of London and developed the capacity to raise money to support the work.

As we will see, for the next 22 years, Ellen Ranyard spent a lot of her time developing the new organization, extending the coverage it offered in London, and broadening the role of her workers. At the same time, she researched and wrote several significant texts exploring the roles of what were subsequently called social workers and district nurses (see, in particular, Ranyard 1859, 1875). As Lizzie Allridge (1895: 126) reported, ‘She wrote right up to the last. The Reading Room of the British Museum was her refuge’, and, luckily, close to her home.

Ellen Ranyard died of bronchitis at home in Hunter Street on February 11, 1879. Just under a month later on March 10, 1879, her husband Benjamin died at the home of one of his brothers (Cedar Lodge, Surbiton) (The Epsom Journal, March 18, 1879). Both were buried in Norwood Cemetery (Boase 1896).

Bible women

One of Ellen Ranyard’s best-known innovations was the idea of the ‘Bible woman’.

This missionary cum social worker, a working class woman drawn from the neighbourhood to be canvassed, was to provide the “missing link” between the poorest families and their social superiors… Given a three month training… in the poor law, hygiene, and scripture, Mrs Ranyard agents sought to turn the city’s outcast population into respectable, independent citizens through an invigoration of family life. (Prochaska 1988: 49)

By 1867, 234 Bible women were working in London. They were the first group of paid social workers in Britain.

From the start in The Seven Dials it became clear that Bibles were not all that was needed. Ellen had appointed a local woman – Marian – as the first Bible Woman. Together, they quickly recognized a need for cheap recipes for nutritious food; and the capacity to lend saucepans so that it could be cooked. They also set up a clothing club and a sewing meeting. As Allridge put it, ‘little by little, there grew up a Domestic as well as a Bible mission’ (1895: 123).

The uniqueness of Ranyard’s approach has been highlighted by Frank Prochaska (1988: 49). Basically, the Mission used postal districts and mapped them. As we have seen, Ellen Ranyard they also assigned Bible women to their own neighbourhoods.

Familiarity with a district was thought essential if the immediacy of parish life was to be recreated… Being local, the Bible women could walk about their districts inconspicuously, though they were occasionally insulted and some of them had buckets of slop thrown over them. From the beginning, the Mission instructed the Bible women to sell Bibles and to provide domestic advice to wives and mothers. It was argued that the reform of mothers was the most crucial task if the condition of the poor was to be improved. Selling Bibles was found to be much easier when combined with tips on cooking, cleaning, and other household matters. Before long, the poor subscribed to schemes to pay for clothing and furniture… Alert to the dangers of indiscriminate relief, she wished to give every encouragement to self-help.

Ellen followed the usual evangelical line of viewing social distress as the outcome of individual failings or personal misfortune rather than something more structural. She believed passionately in the importance of deepening people’s religious knowledge and in conversion. However, she did at least recognize that this was not a wholly individual matter and argued that it was important to work at creating a Christian environment. That environment would ‘transform the poor into accountable, self-respecting members of society’ (ibid.: 50). Much like the YMCA missionaries, she wanted the Bible women to work with people of all faiths. However, she was deeply distrustful of Catholicism and, as a result, she instructed the ‘Bible women’ not to work with people within this Christian tradition.

Bible nurses

In 1868, the Bible women were followed by another Ranyard innovation – ‘Bible nurses’. These were, effectively, the first district nurses in London. Ellen had recognized that local Bible Women could only take things so far. It took a considerable effort on Ellen’s part, to convince hospitals of the need for them to provide a training programme. The Bible nurses were trained in London hospitals and undertook a probationary period (Prochaska 1988: 52). Like the Bible women they were working class and carried a Bible with their medical supplies.

Supervised by lady volunteers they carried out duties which blended preventive work, patching up, and religious proselytising. These duties included referring patients to doctors and local hospitals, inspecting infants in mother’s meetings, and encouraging medical self-help among the poor. [Mrs Ranyard] was very much aware of the degree to which the poor looked after one another in emergencies and hoped to extend and improve these traditions with nursing assistance and advice. (op. cit.)

Within 25 years the Mission had over 80 district nurses in London (in 1894 they made 215,000 visits to almost 10,000 patients). As nurse training developed in hospitals, the Mission withdrew from training in 1907 (see Platt 1937). Ranyard Nurses continued after the introduction of the National Health Service in 1948 but worked in cooperation with London County Council District Nursing Service in South London In 1965 they were taken over by the district nursing services run by London boroughs (London Metropolitan Archives 2000)..

Management, organization and raising money

A further innovation introduced by Ellen Ranyard was how she organized the administration of the work. She recruited middle-class superintendents, usually from outside the neighbourhood, to manage and oversee the programme. These superintendents paid the Bible women and monitored the various Mothers’ meetings they organized in mission halls etc. To Ellen, the relationship between the supervising lady and the bible-woman was ‘our kind of sisterhood’. The key rule was that, ‘a poor woman is the best agent for carrying [the Bible] to women in those depths, and that she requires the constant aid and sympathy of a Christian sister from the educated classes’ (See Ranyard 1875 p. 296).

With the development of Bible nurses, what began as The London Bible and Domestic Female Mission then became The London Biblewomen and Nurses Mission in 1868. Later, in 1917, it became known as The Ranyard Mission and by 1953 it was known as the Ranyard Mission and Nurses (you can view the Annual Reports 1897-1964 in the London Metropolitan Archives). As can be seen, the growth of the organization and the administration of its work created a considerable amount of paperwork.

The success of Ellen Ranyard’s (1852) book – The Book and Its Story: A Narrative for the Young – and her involvement in British and Foreign Bible Society led her to help establish and then edit a new monthly magazine in 1856 – The Book and its Missions past and present. It was designed for the membership of the Bible Society – but was not an official publication as the Society’s constitution did not allow for this. With the establishment of The London Bible and Domestic Female Mission, the magazine began to carry material on London Bible Women (catalogued in the London Archives listing of Ranyard Mission documents). This was an important move, as it raised the profile of, and need for, Bible women and, later, the Bible nurses. In turn, this encouraged the giving of donations to support the work.

The magazine continued to 1864, In 1865, the magazine was renamed. Now called The Missing Link Magazine, or Bible Work at Home and Abroad it was ‘wholly devoted to furthering her mission’ (Boase 1896). It was published for a further 14 years (closing in 1879). Material from the early days of the magazine was reworked to be included in Ellen Ranyard’s (1857) book The Missing Link or Bible-Women in the Homes of the London Poor. The book starts, ‘This book scarcely requires a preface. The greater part has already had many readers’.

The headquarters of the Mission was initially in Hunter Street (presumably in the Ranyard family home) and then moved round the corner to Regent Square. It later transferred to 2 Adelphi Terrace, by the Embankment Gardens. This area was home, at various times, to a significant number of institutions concerned with social reform (see the Exploring informal education walk).

Bible Women + Bible Nurses as informal educators

Fairly early in The Missing Link (the book) there is a section called ‘Marian’s tea-party in St Giles’. Marian was the first Bible Woman. It begins as follows:

The second month of Bible visits had not passed away before a desire arose in the heart of the persevering visitor, and of the friend to whom she continually brought her reports, to do something to place these people in a condition to profit by the Book they were willing to buy. It was almost impossible to sit down to read the Bible to them in the midst of their dirt. “I should like, if you had no objection, ma’am,” said Marian, “to ask a few of them to tea with me – my husband is in the country – and then I could have a little talk with them on their ways, and how to mend them.”

The lady cordially entered into this proposal. She told Marian that any small expense to which the tea might put her should be met, and awaited the result. This, perhaps, is best given in the form of a conversation as it occurred between the parties. (Ranyard 1859: 36)

The ‘lady’ here, presumably, was Ellen Ranyard.

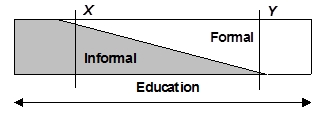

The approach being described here was not instructional. While Marian clearly has an agenda, but in this form, the subject matter has to flow from interaction. Later in the book, Ellen talks about how things are often better ‘conveyed by conversation rather than by reading’ (op. cit.: 245). Elsewhere on infed, we explore the nature of such informal education. It can be defined as ‘the wise, respectful and spontaneous process of cultivating learning. It works through conversation and the exploration and enlargement of experience’ (Jeffs and Smith 2011). Following on from this, practitioners have to:

operate in a wide range of settings – often within the same day. These include centres, schools and colleges, streets and shopping malls, people’s homes, workplaces, and social, cultural and sporting settings.

look to create or deepen situations where people can learn spontaneously, ‘explore and enlarge experience’, and make changes. (op. cit)

If we examine the practice of informal educators such as youth workers and social pedagogies, we can see they have to both pick their moments for intervention, and decide how to do it. A lot of the time it may be the odd question or statement to stimulate thinking, at others it could be a more formal interlude or ‘teaching moment’.

Christian educators such Bible women and nurses have to work in a different way than ‘that of the upfront preacher/evangelist’ (Ellis 1990). The bulk of their work is not based on ‘delivering a curriculum’ but in cultivating exploration and engagement. Josephine Macalister Brew, who wrote the first full-length book on informal education (1946), described this process at work in youth work:

Only by the slow and tactful method of inserting yourself unassumingly into the life of the club, not by talking to your club members, but by hanging about and learning from their conversation and occasionally, very occasionally, giving it that twist which leads it to your goal, is it possible to open up a new avenue of thought to them (1943: 16).

Bible women and nurses had to mix instruction with something quite different.

Conclusion

Ellen Ranyard’s contribution to the development of social work, nursing and community work has not been properly recognized. It might be that the focus within evangelicalism has tended to put some commentators off. However, it is interesting to note that a key general principle adopted both for Bible Women and Bible Nurses was that ‘working together in a Bible-mission in the regions of poverty, misery, and crime, is of more importance than any of our differences as to ecclesiastical organisation’ (op. cit.). That said, how Ranyard recruited, trained and deployed working-class workers was a significant innovation and a landmark in the development of practice.

This area of London was later where several other women featured on these pages sought to combat the poverty, discrimination and lack of opportunity associated with it. Many of them were outsiders. The group includes:

Maude Stanley (1833-1915) developed district visiting and work with, and the provision for young women around the Five Dials and in Soho (see Stanley 1878, 1890). She adopted Ellen Ranyard’s approach and used local people as helpers.

Lily Montagu (1873-1963) was one of the founders of the National Organization of Girls Clubs (now Youth Clubs UK) and a key figure in the development of Jewish youth work. She believed that visiting the poor and club members should be based in friendship, not investigation (see Jean Spence 1999). Lily Montagu undertook a significant amount of club work in Dean Street and Frith Street in Soho – a few minutes walk from Seven Dials.

Mary Neal (1860–1944) and Emmeline Pethick (1867–1954) came to work as ‘Sisters’ in the West London Mission in the 1890s. Mary Neal became an important figure in the breathing of new life into the English folk music and dance movement and was a key figure in the establishment of the first UK play centre (with Mary Ward, below), Emmeline Pethick went on to become the treasurer and a key organizer with the Pankhursts of the English Suffrage Union (see Atherton 2019, 2024).

Mary Augusta Ward (1851-1920) was a key pioneer in the settlement movement and the development of provision for children with disabilities and for play. She established a women’s settlement nearby in Gordon Square in 1890, which moved to a new building (Passmore Edwards Settlement) on Tavistock Place (which crosses Hunter Street) in 1897.

All but Mary Augusta Ward are included in our informal education walk in central London.

Further reading and references

Alldridge, L. (1890) Florence Nightingale, Frances Ridley Havergal, Catherine Marsh and Mrs Ranyard (“LNR”) 5e, London: Cassell and Co. 128 pages. Contains a potted (30-page) biography. Available in the Internet Archive and here in the infed archives.

Atherton, K. (2019). Suffragette Planners and Plotters. The Pankhurst/Pethick-Lawrence Story. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books.

Atherton, K. (2024). Mary Neal and the Suffragettes Who Saved Morris Dancing. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books.

Binfield, C. (1983). George Williams and the YMCA. A study in Victorian social attitudes. London: William Heinemann Ltd.

Boase, G. G. (1896). Ellen Henrietta Ranyard in Sidney Lee (ed). Dictionary of National Biography Vol. 47. London: Smith, Elder & Co. [https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Ranyard,_Ellen_Henrietta].

Brew, J. Macalister (1943). In The Service of Youth. A practical manual of work among adolescents. London: Faber.

Brew, J. Macalister (1946). Informal Education. Adventures and reflections. London: Faber.

Ellis, J. (1990) Informal education – a Christian perspective in Jeffs, T. and Smith, M. (eds.) (1990). Using Informal Education. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. [https://infed.org/mobi/using-informal-education-chapter7-informal-education-a-christian-perspective/].

Jeffs, T. and Smith, M. K. (2005). Informal Education. Conversation, democracy and learning, Ticknall: Education Now.

Jeffs, T. and Smith, M. K. (1997, 2005, 2011). ‘What is informal education?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/what-is-informal-education/. Retrieved: April 4, 2025].

Lewis, D. M. (1985). Lighten Their Darkness: The Evangelical Mission to Working-Class London, 1828-1860 London: Greenwood Press. (Reprinted by Paternoster, 2001).

London Archives, The (undated). Ranyard Mission and Ranyard Nurses. [https://search.lma.gov.uk/LMA_DOC/A_RNY.PDF, retrieved April 1, 2025]

London Metropolitan Archives (2000) History of Nursing. Major sources in the London Metropolitan Archives, http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/leisure_heritage/ libraries_archives_museums_galleries/lma/pdf/nursing.PDF.

Montagu, L.H. (1941) My Club and I: The Story of The West Central Jewish Club, Herbert Joseph, London.

Platt, E. (1937) The Story of the Ranyard Mission 1857-1937, London: Hodder and Stoughton. 128 pages. Account of the work of the Mission charting the shifting emphases.

Proshaska, F. (1988) The Voluntary Impulse. Philanthropy in modern Britain, London: Faber and Faber. 106 + xv pages. This is a concise and insightful exploration of the development of philanthropy in Britain. Proshaska is particularly good at bringing to light the many forms that working-class philanthropy took, the relationship of evangelicalism and liberalism in the development of more formal philanthropy, and in highlighting the continuities and resilience of charitable traditions. The book includes a very helpful discussion of Ellen Ranyard’s work. See, also, his (1980) Women and Philanthropy in Nineteenth-Century England, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 126-130

Prochaska, F. K. (1987) ‘Body and Soul: Bible Nurses and the Poor in Victorian London’, Historical Research, vol. 60, pp. 337–48.

Ranyard, E. N. (1852). Nineveh and its relics in the British Museum. By the author of the “Border Land.” Birmingham: J. Broom.

Ranyard, E. N. (1853, 1863). The Book and Its Story: A Narrative for the Young. New York: Robert Carter and Brothers.

Ranyard, E. N. (1859). The Missing Link; Or Bible-Women in the Homes of the London Poor. London: James Nisbet and Co. [https://books.google.com/books/download/The_Missing_Link_Or_Bible_Women_in_the_H.pdf?id=xVGvdfdxRPEC&output=pdf. Retrieved June 27, 2024].

Ranyard, E. N. (1875). Nurses for the needy, or Bible-women nurses in the homes of the London poor, by L.N.R. London James Nisbet and Co. [https://archive.org/details/nursesforneedyo00ranygoog Retrieved March 29, 2025].

Ross, Ellen (ed.), ‘Ellen Henrietta Ranyard’, in Ellen Ross (ed.), Slum Travelers: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860-1920 (Oakland, CA, 2007; online edn, California Scholarship Online, 22 Mar. 2012), https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520249059.003.0019, accessed 27 June 2024.

Spence, J. (1999). Lily Montagu, girl’s work and youth work, The encyclopaedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/lily-montagu-girls-work-and-youth-work/].

Stanley, M. (1878) Work About the Five Dials, London: Macmillan and Co. See extract in the archives.

Stanley, M. (1890) Clubs for Working Girls, London: Macmillan. (Reprinted in F. Booton (ed.) (1985) Studies in Social Education 1860-1890, Hove: Benfield Press.

Williamson, L. (1996) ‘Soul Sisters: The St John and Ranyard Nurse in Nineteenth-Century London’, International History of Nursing Journal, vol. 2, no. 2 (winter 1996), pp. 33–49.

Williamson, L. (2004), Ellen Henrietta Ranyard [née White] in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 60-1.

Smith, M. K. (2001, 2003, 2025). ‘Ellen Ranyard (“LNR”), Bible women, district nurses and informal education’. The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [https://infed.org/mobi/ellen-ranyard-lnr-bible-women-and-informal-education/. Retrieved: insert date]

© Mark K. Smith 2001, 2003, 2025

Pictures: the images of Ellen Ranyard are both understood as being in the public domain.